A History of Oxford County's Library Services

1. Ontario Before the Age of County Libraries (1800-1899)

1800 | The earliest known library in Upper Canada opens in Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake, ON). It's a subscription library housed in the town's courthouse.

1835 | Woodstock opens its first library, a subscription library. It's the earliest known library established in Oxford County.

1855 | Ingersoll opens its first library. It too is a subscription library but operates out of a room at a local public school.

1882 | Ontario passes its Free Libraries Act, which allows towns and cities to establish free, tax-supported public libraries.

1883 | Having passed its by-law January 1, Toronto's public library becomes Ontario's first free public library. Guelph's public library, its by-law passed on January 18th, becomes Ontario's second free public library. And, although it's not a free library, the village of Embro establishes its first library the same year.

2. The Call for County-Level Library Service Grows (1900-1936)

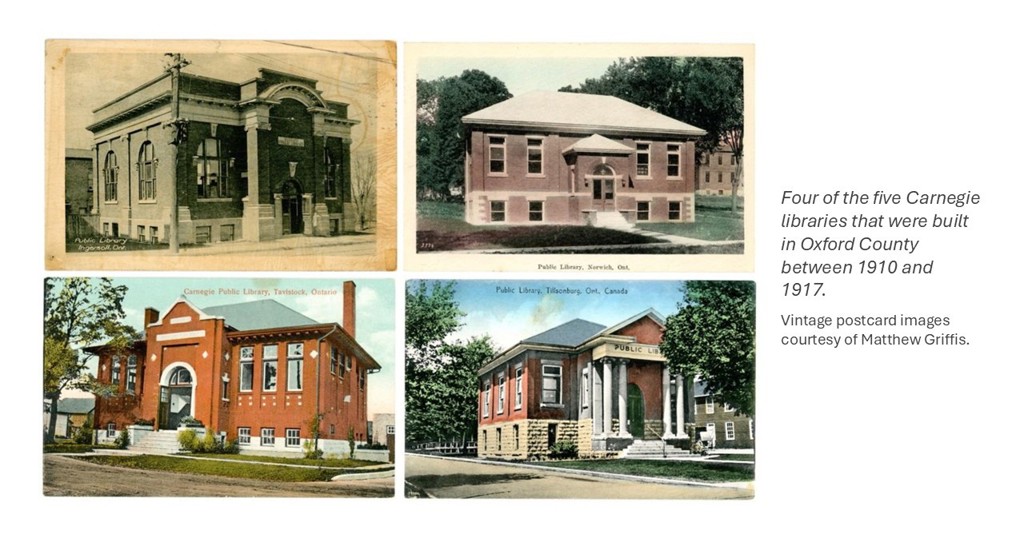

1900-17 | Scottish-born American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie launches a library building program that produces over 2,500 library buildings (known informally as "Carnegie libraries") around the world. And of the 125 Carnegie libraries built in Canada, 111 are located in Ontario and 5 in Oxford County. Woodstock's Carnegie library opens in 1909; Ingersoll's opens in 1910, Tillsonburg's in 1915, Norwich's in 1916, and Tavistock's in 1917. A sixth, which was planned for Otterville and was to serve South Norwich township, was never built.

1909 | Recognizing that its town and city public libraries were not sufficient to serve the entire state's population, California becomes the first American state to allow county-wide public library systems to form. This pioneering law, titled An Act to Provide County Library Systems, is replaced in 1911 with the more extensive County Free Library Act.

1910 | The journal Public Libraries calls California's new county library plan “probably the most radical piece of library legislation ever enacted”. In his annual report to the Minister of Education, Ontario's Inspector of Public Libraries, Walter Nursey, acknowledges California's new law, but with Ontario in mind, adds: “[I]t is too soon to advocate, much less adopt a system that by certain United States authorities has not proved the success claimed for it.”

1912 | At the annual Niagara Institute at Beamsville, W.H. Arison, the chairman of the Niagara Falls (Ontario) Public Library's board, praises California's new model (calling it the “most effective county [library] system existing at this time”) and encourages its adoption in Ontario. This is the earliest proposal on record for the development of county library services in Ontario.

1913 | As more free libraries form in Ontario's villages, towns, and cities, library authorities continue to debate the merits of county-level library service. In a 1914 paper titled "The Public Library in Every Municipality", Norman Gurd of the Sarnia Public Library suggests that if public libraries organize at a unit higher than town or village level, that it be at the township level.

1916-20 | During their bid for a Carnegie library, South Norwich Township and the village of Otterville convince Queen's Park to amend the existing Public Libraries Act to allow township public libraries. A few years later, the village of Millbrook makes a similar application for the residents of Cavan Township. Although neither Carnegie library is built, the 1916 amendment becomes part of the revised Public Libraries Act of 1920. (No township public libraries form in Ontario until the 1940s, however.)

1920 | At least 22 American states have passed laws allowing some form of county-level library service to operate: California, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana (for parish libraries), Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Some states follow the decentralized California model; others make a single library (usually located in the county seat) available to all residents of the county.

1928 | In his annual report for 1928, Ontario's Inspector of Public Libraries, Walter O. Carson, notes that while 71% of Ontario's public libraries serve village or rural districts, 900,000 Ontarians still lack access to library services. "Small units will never solve the problem," Carson opines. "[T]he time seems to have arrived when there should be provision for larger library units," he says, adding: "The county as a unit has proven satisfactory in Great Britain and parts of the United States."

1931 | In its August issue, the Ontario Library Review examines the progress of California's county library system since its inception in 1909.

1932 | Under the leadership of the Sarnia Public Library's Dorothy Carlisle, Ontario's first county library association forms in Lambton County. Its initial membership comprises seven town and village libraries but later expands to eighteen. Based on successful models in England and parts of the United States, county library associations do not operate on the “California model” but instead as collectives that rotate shared collections among independent member libraries.

1933 | F.C. Jennings, the new the provincial Inspector of Public Libraries, writes favourably in his annual report of the county library association model. Although Ontario's Public Libraries Act does notrecognize any form of county library service, Jennings authorizes annual grants for any county associations that form in Ontario.

1933 | F.C. Jennings, the new the provincial Inspector of Public Libraries, writes favourably in his annual report of the county library association model. Although Ontario's Public Libraries Act does notrecognize any form of county library service, Jennings authorizes annual grants for any county associations that form in Ontario.

1934 | The Middlesex County Library Association forms and holds its first meeting in December. It comprises fifteen member libraries.

1935 | The Lambton County Library Association launches its “traveling library”, a special trailer attached to the back of a motor car. This is the earliest known traveling library in Ontario not pulled by horses.

1936 | Her work with county libraries now well-known outside Ontario, Dorothy Carlisle is invited to serve on committees of the American Library Association (headquartered in Washington, DC).

At a February meeting of the Thamesford Public Library's board, librarian R.E. Crouch of the London Public Library delivers a paper titled “County Library Associations and How One Worked in Middlesex County”. In April, the Ontario Library Association advocates for legislative changes that recognize the needs of county library associations. The Elgin County Library Association forms by late spring.

From September through November, and with further encouragement from London's R.E. Crouch, library representatives from across Oxford consider forming a county library association. By late fall, as many as seventeen of Oxford's libraries show interest in the plan.

In a fourth and final meeting held on November 13th in Woodstock, representatives from ten of the county's public libraries decide to form an Oxford County Library Association. The Woodstock Public Library volunteers to serve as a central central distributing point. "We are hoping, perhaps rather too optimistically," Woodstock's Blythe Terryberry writes at the time, "that the [Oxford County Library] Association will be launched and underway by the new year".

3. The Oxford County Library Association (1937-47)

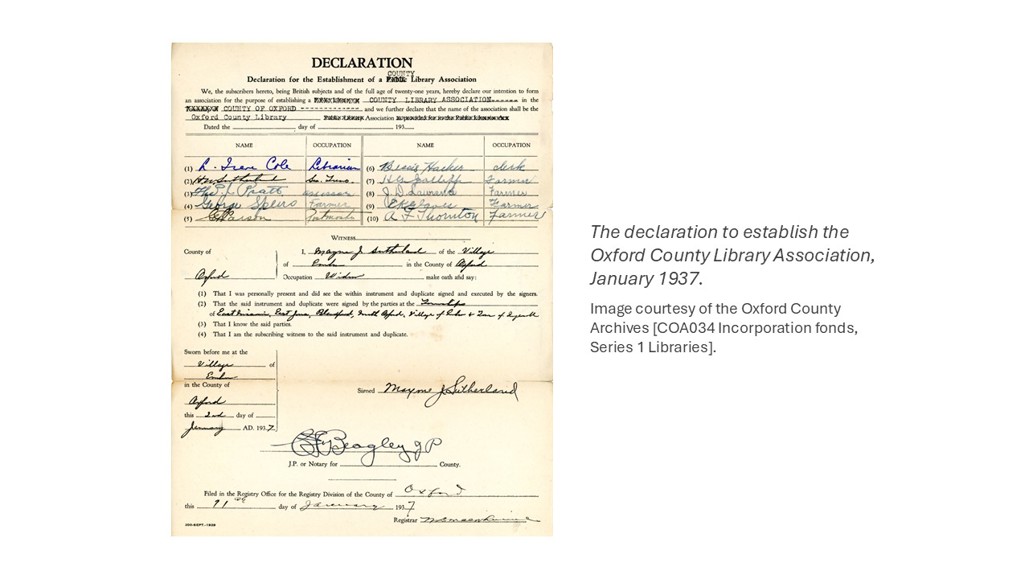

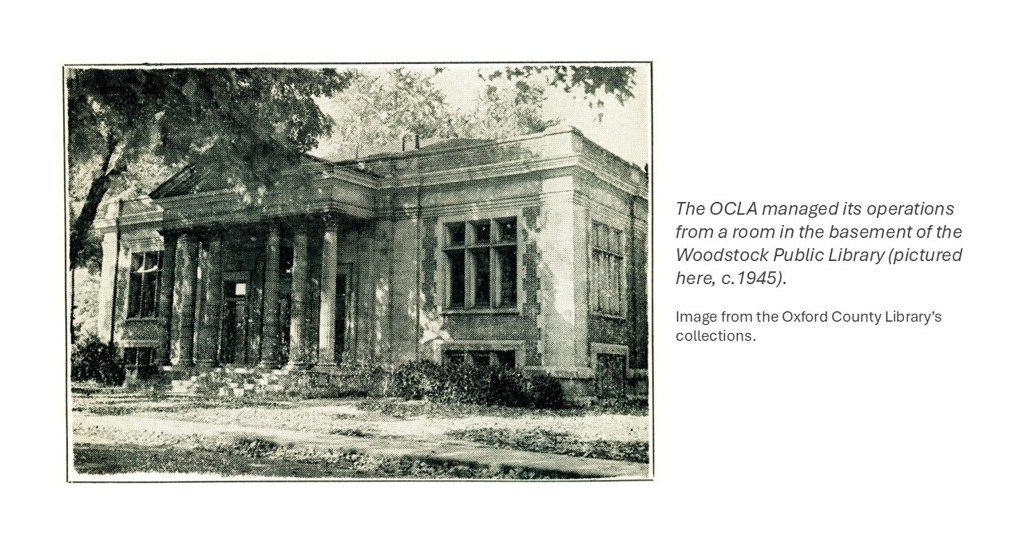

1937 | In January, the officers of the Oxford County Library Association (OCLA) submit charter documents and to establish the new collective. They hold their first meeting on February 12th. The Association's inaugural members include the libraries of Beachville, Burgessville, Drumbo, Embro, Hickson, Ingersoll, Kintore, Mount Elgin, Plattsville, Princeton, and Thamesford. Blythe Terryberry, Chief Librarian of the Woodstock Public Library, and Irene Cole, Chief Librarian of the of the Ingersoll Public Library, co-supervise the Association's operations, using space in the Woodstock library's basement for an office. The annual fee for member libraries is $15.00.

To rotate shared collections, representatives from each member library meet every three months at the Woodstock library to exchange books. (The books are kept in cardboard boxes, and representatives exchange boxes from the trunks of their cars.) Once books have been exchanged by all members, the OCLA places them permanently at various member libraries.

In July, former public library administrator Angus Mowat begins his tenure as Ontario's Inspector of Public Libraries.

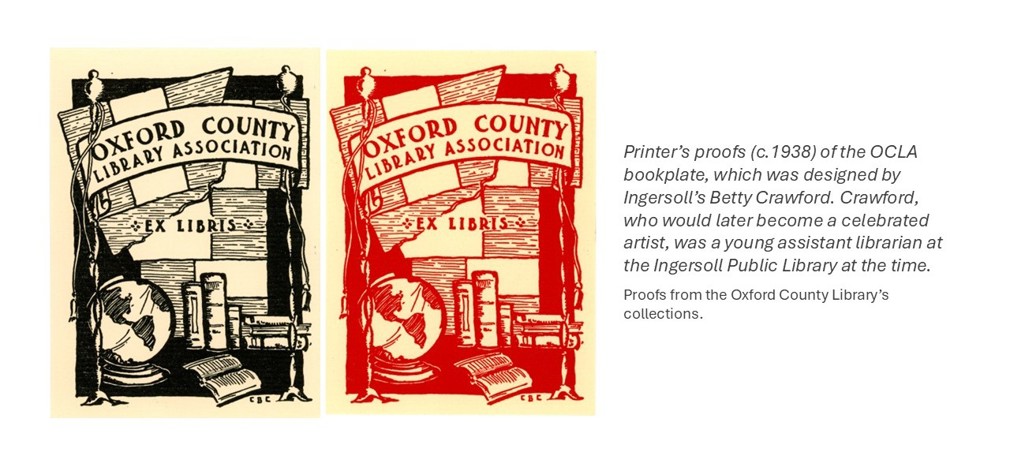

1938 | The OCLA introduces a custom bookplate, to be pasted inside the covers of all books in the OCLA's collections. Betty Crawford, who joined the Ingersoll Public Library staff the previous year, designs the plate. As she'll explain years later to the Ontario Library Review, "[T]he background [is] a map of the county, against which is an atlas, and the books by which the world is interpreted for us".

1939 | According to Inspector Mowat's annual report, at least four fully chartered county library associations exist in Ontario, including Lambton, Middlesex, Elgin, and Oxford.

1940 | The Simcoe County Library Association forms early in the year. And, after having organized unofficially in 1936, the Essex County Library Association establishes itself as Ontario's sixth fully chartered county library association.

By the end of the year, the OCLA comprises eleven member libraries.

1941 | The Huron County Library Association forms. Betty Crawford becomes Chief Librarian of the Ingersoll Public Library and assumes co-managership (with Blythe Terryberry) of the OCLA.

1942 | The Kent County Library Association forms in May.

In his annual report for 1942, S.B. Herbert, Ontario's Acting Inspector of Public Libraries, observes the progress of Ontario's eight county library associations. "This completes a solid block in the western part of old Ontario," he writes, "and with Simcoe County Library Association nearer the centre of the province, it is hoped the influence will spread, especially towards the east, as at present there are no County Library Associations between Toronto and Ottawa -- a section in which there is undoubtedly a need for such organizations".

1943 | By this time, Oxford County has agreed to grant the OCLA $50 annually.

1944 | Inspector Mowat drafts revisions to the existing Public Libraries Act that will allow full county level public library systems to form. His work continues into 1945.

1945 | The Bruce County Library Association forms.

1946 | The Welland County Library Association forms. It is Ontario's eleventh such association.

1947 | In April, the Public Libraries Amendment Act of 1947 receives royal ascent, with changes effective January 1948. But the new law doesn't include provisions for county-level public libraries. Instead, it requires all existing county library associations to re-establish themselves as "cooperatives". This new law also requires county councils to authorize library cooperatives by passing a bylaw and appointing county-level library boards. County councils may supplement annual provincial grants but are not to exceed the province's annual legislative amount.

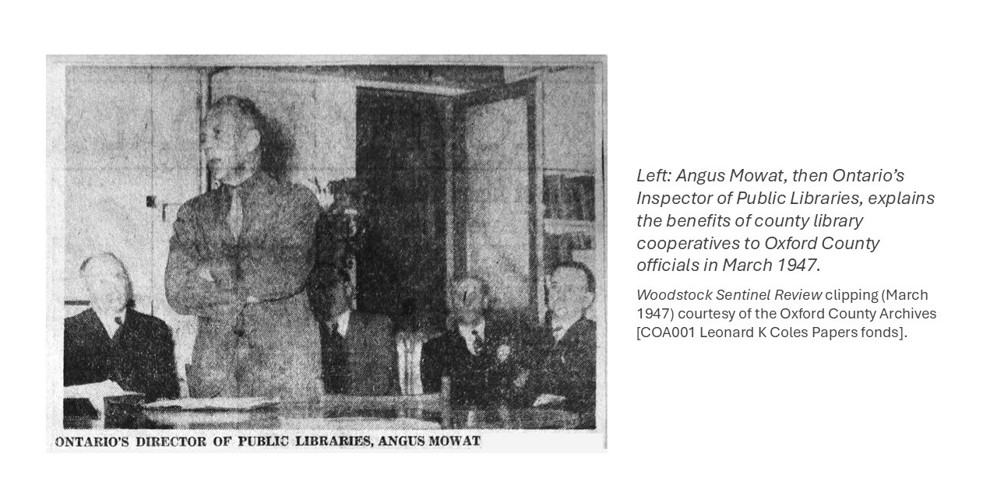

Angus Mowat, the Director of Public Libraries in Ontario, attends a meeting of the Oxford County Library Association in June and explains Ontario's forthcoming laws for county library services. In September, County Council recommends that the "formation of the [Oxford] County Library Cooperative" be filed, in anticipation of the Libraries Act amendments.

4. The Oxford County Library Cooperative (1948-64)

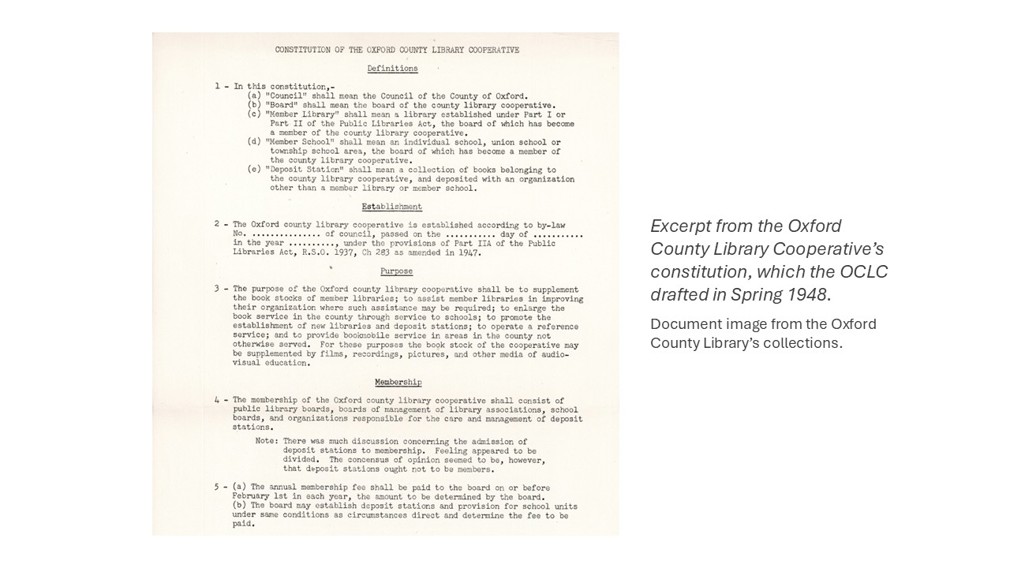

1948 | The Oxford County Library Cooperative (OCLC) begins drafting its constitution in January. Its purpose (as described in a 1949 report) is to "distribute books to the local [public] libraries, schools, and other interested groups". The Woodstock Public Library's Blythe Terryberry, who co-managed the former library association, serves as the OCLC's interim librarian and runs the new cooperative from the basement of the Woodstock library.

In April, the OCLC's inaugural board of trustees holds its first meeting and adopts its constitution. The OCLC's first annual budget is $1,000 with $700 of that to be spent on shared collections. Both the County Council and the newly formed OCLC board recommend that all public libraries in the county join the cooperative. In June, County Council makes the cooperative official by passing By-Law 1423 and agreeing to grant the OCLC $50 a year.

1949 | In the spring, Louise Krompart is hired as the OCLC's first County Librarian. She begins on April 1st. (Born Louise Fairlie Huffman in Woodstock, Krompart had served the Woodstock Public Library as an assistant librarian until 1930, then as its Chief Librarian until 1934.) On the advice of Angus Mowat, Krompart visits several county library cooperatives in the region to observe how they operate.

In the summer, the OCLC relocates its operations to a single room in the basement of the county courthouse in Woodstock. By this time, sixteen of the county's public libraries have joined the OCLC but by the end of the year all seventeen libraries will have joined. The OCLC also opens a deposit station in the hamlet of Bright.

Just as in the OCLA's last years, the OCLC distributes books by automobile. Motorized book vans exist (first in Ontario was the Huron County Library Association's van of 1947) but are expensive.

In October, Louise Krompart begins giving "book talks" to the county over CKOX radio in Woodstock. By end of 1949, the OCLC's collections total 2,511 books.

1950 | After receiving more than 60 applications for school service, the OCLC begins supplying books to many of the county's classrooms. After the Lakeside Public Library joins, the OCLC comprises eighteen town libraries. The OCLC's collection, based largely on the books it inherited from the former Oxford County Library Asosciation, totals just over 2,000 volumes.

1950 | After receiving more than 60 applications for school service, the OCLC begins supplying books to many of the county's classrooms. After the Lakeside Public Library joins, the OCLC comprises eighteen town libraries. The OCLC's collection, based largely on the books it inherited from the former Oxford County Library Asosciation, totals just over 2,000 volumes.

1951 | Mrs. W.G. (Christine) Crocker joins the OCLC staff in October as Louise Krompart's assistant. (She remains with OCLC until 1965, when she will be hired by the newly formed Oxford County Library. She eventually retires in 1979.) By December, the cooperative's classroom itinerary will include all schools in the county that do not reside close to a local library. "Expansion usually brings a few problems," Krompart notes in her annual report. "We are beginning to feel the need for a bookmobile rather badly. Picking up about 3,000 books in June and returning that many to the schools in September is rather difficult with a car."

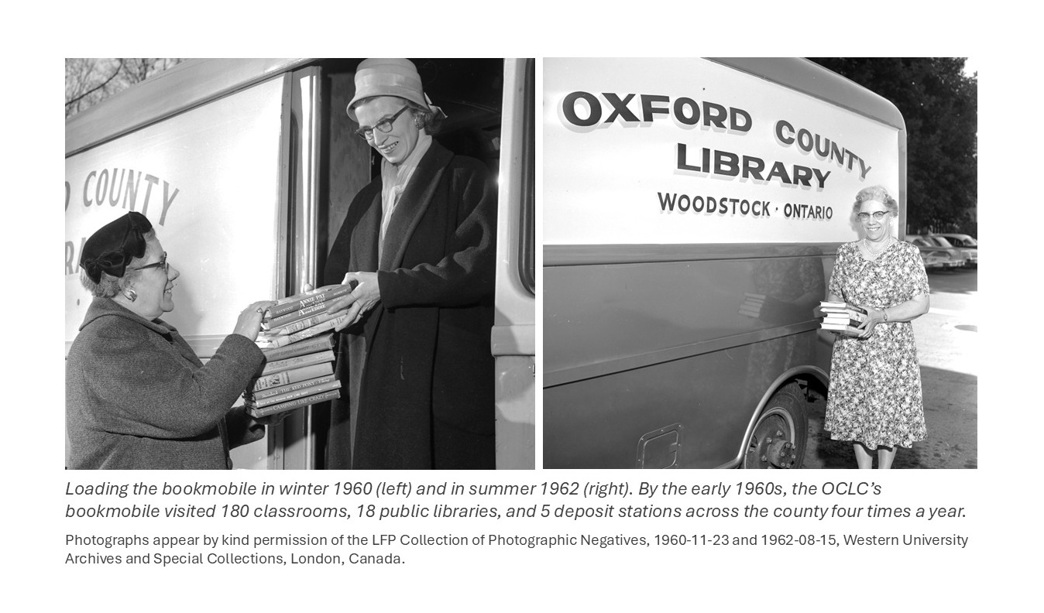

By the end of 1951, as many as thirteen county library cooperatives operate in Ontario. Interest in motorized bookmobiles increases as The Books Drive On!, a short film made years earlier about the Huron County Library's bookmobile service, is screened across Canada and the United States. (The Huron County Library eventually receives a letter from the federal Department of Immigration and Citizenship in Ottawa informing them that the film is being shown overseas to prospective immigrants.)

1953 | In March, the OCLC's new bookmobile (a motorized bookvan virtually identical to the Huron County Library's) makes its inaugural run, ending the old routine of distributing books by car. The bookmobile travels three weeks at a time, delivering new books and rotating shared collections among all member libraries and county schools. It completes this 3-week, thousand-mile run four times a year: in March, June, Aug-Sep, and Nov-Dec. Louise Krompart's retired husband, Stanley, drives the new bookmobile.

By this time, the OCLC manages about 8,000 books and serves all eighteen of the county's public libraries (plus four deposit stations). To help its growing operations, the OCLC relocates to a larger space in the county courthouse's basement: two rooms, one with an outlet for loading the bookmobile.

1955 | According to the Woodstock Sentinel-Review, the OCLC's collections now total about 12,000 volumes. The bookmobile continues its regular visits to the county's public libraries and 148 classrooms across the county.

1955 | According to the Woodstock Sentinel-Review, the OCLC's collections now total about 12,000 volumes. The bookmobile continues its regular visits to the county's public libraries and 148 classrooms across the county.

1956 | The Waterloo County Library Cooperative forms. Its librarian, Mr. Gowing, and members of the new cooperative's board visit OCLC headquarters several times for help and advice.

1958 | After launching a county-wide "Book Review Contest" for students in grades 7 and 8, the OCLC receives eighty-five entries. This is the earliest evidence on record of county-wide library programming in Oxford. Two staff members from the Woodstock Sentinel-Review serve as judges.

1959 | Ontario passes its Public Libraries Amendment Act 1959, with changes effective January 1960. Under the new law, pre-existing library cooperatives may continue, but counties may form county-wide public libraries if at least 75% of a county's municipalities favour and are willing to join such a system.

The work of longtime provincial library director Angus Mowat, the Public Libraries Amendment Act 1959 signals Mowat's retirement.

1960 | The Public Libraries Amendment Act 1959 becomes law. However, no counties take steps to form county-wide public libraries for a couple years yet. Regional cooperatives form instead.

An OCLC deposit station opens in Sweaburg.

Now an annual program, the "Book Review Contest" for Grades 7/8 students attracts 150 entries, its highest number yet.

1961 | A new deposit station opens in Salford, the OCLC's sixth. In her annual report, County Librarian Louise Krompart mentions some of the potential benefits of establishing a county-wide public library under the new provincial law.

1962 | In response to the province's underwhelming response to the Public Libraries Amendment Act 1959, Ontario passes the Public Libraries Amendment Act 1961-62. Under the new legislation, counties may form county-level public libraries instead of cooperatives if at least 50% of a county's municipalities are willing to join such a system.

The OCLC opens a deposit station in Springford, its seventh. Membership still includes eighteen village and town libraries from across the county. The OCLC also purchases a new bookmobile. By this time, the OCLC bookmobile travels about 4,000 miles to exchange 15,000 books annually. The OCLC's entire collection totals 33,000 volumes.

1963 | Interest in forming county-wide public libraries increases in Ontario. Served by a county library cooperative since the late 1940s, Middlesex County considers reorganizing many of its public libraries into a single, county-wide system.

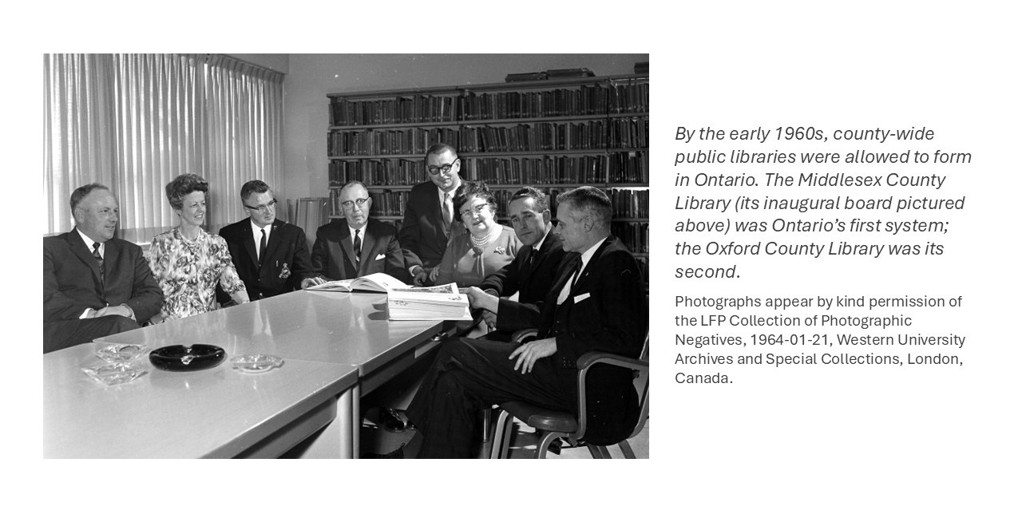

1964 | In January, the Middlesex County Library's inaugural board meets for the first time, making Middlesex the first county in Ontario to establish a county public library. They form a board of trustees at county level but maintain "advisory committees" for each branch in their system.

The Lake Erie Regional Library system forms and includes Elgin, Middlesex, Norfolk, and Oxford counties. Another form of library collective, regional systems exist primarily for interlibrary book sharing.

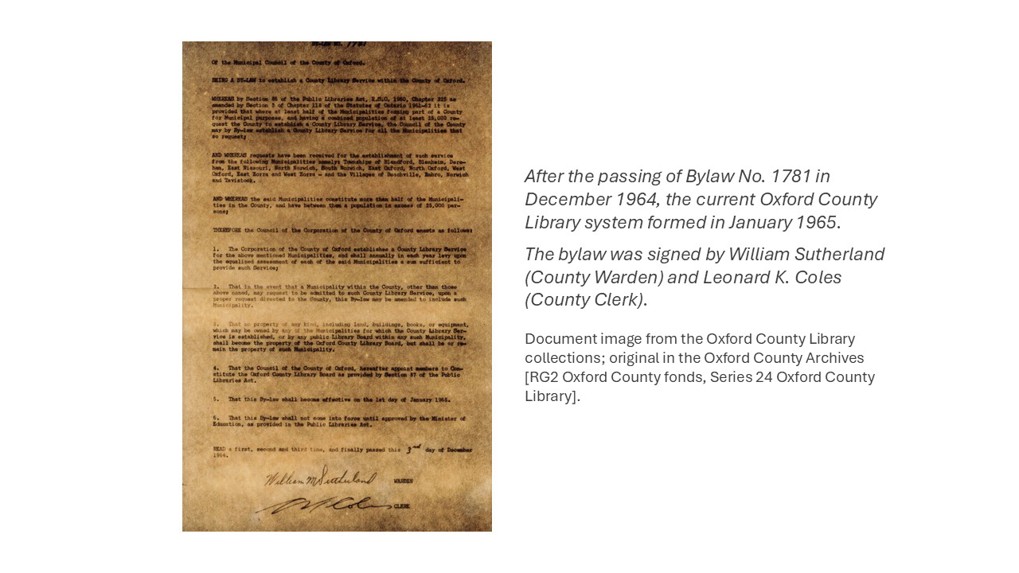

By the fall, Oxford County considers establishing a county public library; and on December 3rd, it passes by-law No. 1781 (effective January 1, 1965) to create the Oxford County Library. The new organization will replace the seventeen year old OCLC and serve the Townships of Blandford, Blenheim, Dereham, East Nissouri, North Norwich, South Norwich, East Oxford, North Oxford, West Oxford, East Zorra, and West Zorra, plus the villages of Beachville, Embro, Norwich, and Tavistock. Only Woodstock, Ingersoll, and Tillsonburg retain their municipal public library systems.

5. The Oxford County Library's First 25 Years (1965-99)

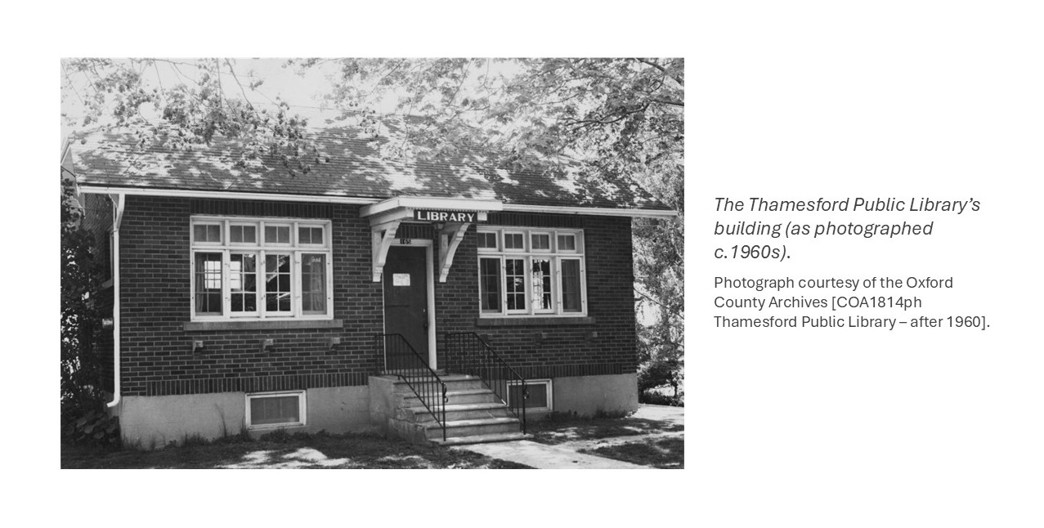

1965 | As of January 1st, the newly formed Oxford County Library (OCL) comprises fifteen branches: Beachville, Brownsville, Burgessville (known then sometimes as the "North Norwich" branch), Drumbo, Embro, Harrington, Hickson, Kintore, Mount Elgin, Norwich, Otterville, Plattsville, Princeton, Tavistock, and Thamesford. In March, the OCL gains a sixteenth branch when the village of Innerkip joins. Deposit stations operate in Bright, Brooksdale, Dereham Centre, Salford, Springford, and Uniondale. This new county-wide system marks the first time that free library service is available in all of Oxford County.

Following the Middlesex County Library's example, the OCL maintains, in addition to its county-level board of trustees, "advisory committees" in each municipality it serves. The new Oxford County Library's headquarters will operate in Woodstock, using the same two rooms in the courthouse basement as used by the former OCLC. And although Ingersoll and Tillsonburg remain independent (town) public libraries, both form a special agreement with the OCL that anyone with an OCL borrower's card may use their services and borrow their books free of charge.

In June, the OCL hires Mary Jane Webb as an assistant librarian in charge of collections. Formerly of the Sarnia Public Library, Webb holds a Bachelor of Library Science (BLS) degree, making her the OCL's first staff member with a university degree in the field.

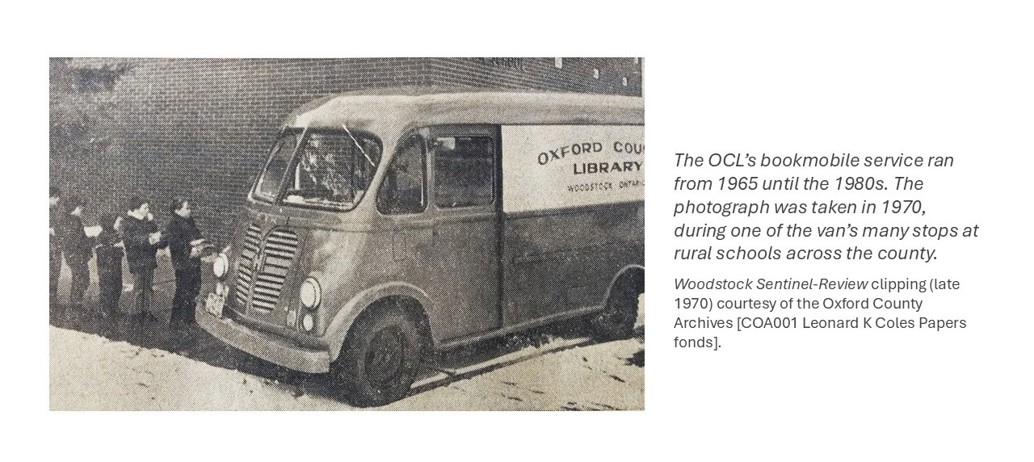

The OCL relaunches the former OCLC bookmobile as the Oxford County Library's. The bookmobile begins visiting the OCL's branches regularly.

Only months after the OCL forms, the drugstore which had housed Drumbo's small library for several years closes permanently, leaving the OCL without a location for its Drumbo Branch. (Nearly two years will pass before the Drumbo Branch reopens in another permanent location.)

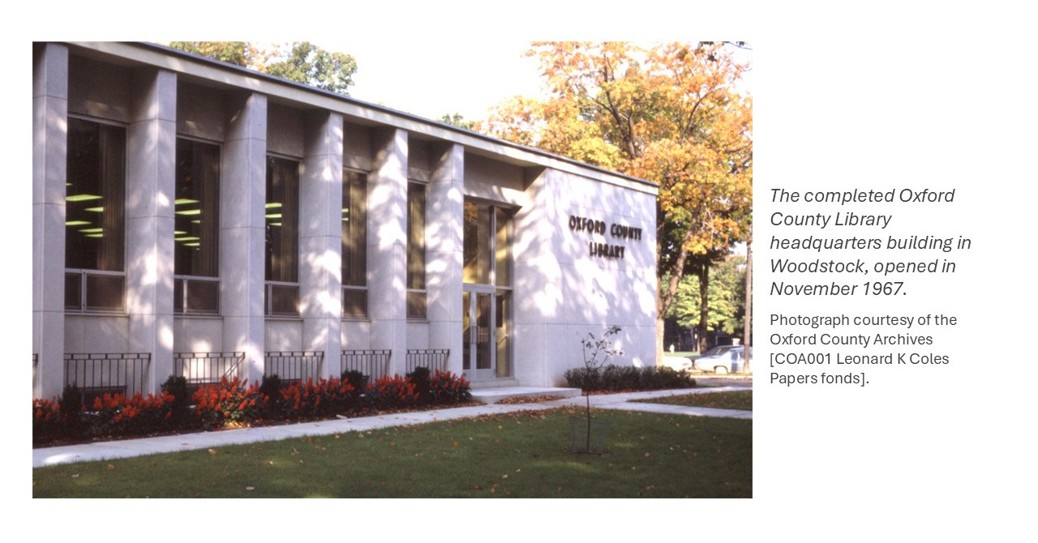

1966 | The OCL bookmobile begins serving classrooms in county schools. In the summer, work begins on the OCL's new headquarters (HQ) in Woodstock. It becomes one of the county's several Centennial building projects. Designed by Duncan Black & Associates, the new HQ will front Graham Street at Buller, where the county jail's east yard had once stood. Construction of the new building will continue into 1967.

1967 | In May, the Burgessville Branch opens in a new building on the corner of Main and Church streets. The OCL also establishes a new branch in East Oxford, in a former school building converted by the Township into municipal offices. Both library branches are among the county's Centennial building projects.

1967 | In May, the Burgessville Branch opens in a new building on the corner of Main and Church streets. The OCL also establishes a new branch in East Oxford, in a former school building converted by the Township into municipal offices. Both library branches are among the county's Centennial building projects.

The OCL opens its newly completed headquarters building in November. Called the "Centennial Library", the new building at 93 Graham Street in Woodstock cost $200,000 and contains the library administrative offices, meeting rooms for the county library board, space for centralized collections processing, and a dedicated bookmobile garage at the building's southwest corner.

1968 | Because of its proximity to the Plattsville Branch, the deposit station at Bright closes.

1969 | Ingersoll dissolves its library board and becomes the OCL's eighteenth branch. The Drumbo Branch reopens at 16 Oxford St. West. Tillsonburg's library remains an independent but "associate" library. Woodstock remains the only municipality in Oxford served exclusively by its own library.

In September, the Ottawa Citizen reports that OCL's bookmobile visits 252 classrooms every three weeks, reaching 11,900 students in public and Catholic schools across the county. Similar articles run in newspapers across the province and continues to appear in Canadian newspapers well into 1970, even in newspapers as far away as the Regina Leader-Post.

1971 | The Ingersoll Branch's supervisor, Betty Crawford, retires and helps establish the Ingersoll Creative Arts Centre.

Crawford had been involved in the county library's operations since the days of the Oxford County Library Association. An Ingersoll native, Crawford graduated from the University of Toronto before returning home to teach in the mid-1930s. Her transition into librarianship reflected two of her great passions, lifelong learning and art. As Ingersoll’s Chief Librarian, Crawford established the Art Club, one of the library’s most popular programs. She spent many vacations completing art classes in the United States and Europe, honing her talents as a watercolourist and printmaker. She contributed to exhibits, won awards, and in 1951 was elected to the prestigious Society of Canadian Painters, Etchers and Engravers. Throughout her career, she met all members of the Group of Seven and even studied with Fred Varley at the Doon School in 1954.

1972 | The Harrington Branch relocates to the village's new community centre, a former school building where Canadian author Ralph Connor is said to have been a student.

By the end of the year, the OCL's collections total just under 165,000 books. Louise Krompart publishes Oxford County Libraries: A Brief History, placing a printed copy at every OCL branch.

1973 | The bookmobile is heavily damaged in an accident on highway 401 and cannot be repaired.

In November, the Thamesford Branch opens a newly constructed extension to their main building.

After 24 years as Oxford's first County Librarian (16 years with the former Oxford County Library Cooperative, plus 8 more with the Oxford County Library), Louise Krompart retires.

1974 | Formerly the OCL's collections librarian, Mary Jane Webb begins her tenure as the OCL's administrator. (Unlike Krompart, however, Webb will be known as the OCL's "Chief Librarian" instead of the "County Librarian".) Christine Crocker remains an assistant librarian. In September, a new bookmobile launches: the third motorized bookmobile to serve the county since 1953.

Throughout the year, a bill to restructure Oxford County into fewer and larger municipalities ("amalgamation") becomes the focus of local news. Once passed, the bill will become law on January 1, 1975.

1975 | Although Oxford's restructuring plan includes no changes to its libraries, a motion is made to combine the OCL, Tillsonburg, and Woodstock library boards into a single system. The motion does not succeed, and Tillsonburg and Woodstock remain separate from the OCL system.

1975 | Although Oxford's restructuring plan includes no changes to its libraries, a motion is made to combine the OCL, Tillsonburg, and Woodstock library boards into a single system. The motion does not succeed, and Tillsonburg and Woodstock remain separate from the OCL system.

In April, the OCL opens a new branch in Foldens.

The OCL's debuts its internal newsletter, Hush, which aims to strengthen communication among staff.

1978 | HQ installs a new teleprinter machine, making “communications amongst all libraries of the system more precise and workable, especially in the interlibrary loan and reference division[s]” (as stated in the OCL’s 1978 Annual Report). This is the earliest instance on record of the OCL embracing modern library automation.

After working in county library services for 27 years, assistant librarian Christine Crocker retires.

1979 | According to a memorandum, the OCL's staff at HQ includes 2 librarians, 1 library technician, 1 secretary, and 1 clerk-typist. The memo adds: "A Xerox copier is of great value."

1981 | The OCL allows the Oxford Historical Society and the Oxford County chapter of the Ontario Genealogical Society to maintain local history and genealogy collections in the HQ building's basement. The library's 1981 annual report mentions that bookmobile service is still active, visiting schools across the county.

1985 | Now comprising a HQ plus 19 public service branches, the OCL, a member of the Ontario Library Consortium, agrees to participate in a three-year project that converts old catalogue records into computer data.

1986 | By fall, the OCL is barcoding its materials and creating its earliest electronic catalogue. ("Automation is coming to the Oxford County Library," notes Mary Jane Webb in her annual report. "[It's s]uch an interesting development in the library profession.")

1988 | After 23 years at Oxford County Library, Chief Librarian Mary Jane Gamble (formerly Webb) retires effective September 1. Sam Coghlan becomes the OCL's new Chief Librarian.

1989 | The OCL receives a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Culture and Communications to hire a writer-in-residence, poet Christopher Dewdney. Dewdney's appointment is part of the province's Writers-in-Libraries Program, established in 1986.

1992 | To address new strategic planning standards, and with substantial input from the Oxford County Library, the provincial government publishes Focus on the Future, a community needs-based assessment manual for county and other rural public libraries to consult when planning services and programs.

1996 | After more than 85 years as a library, Ingersoll’s historic Carnegie building on Charles Street East closes. In October, the Ingersoll Branch reopens in the newly constructed Ingersoll Town Centre building at 130 Oxford Street.

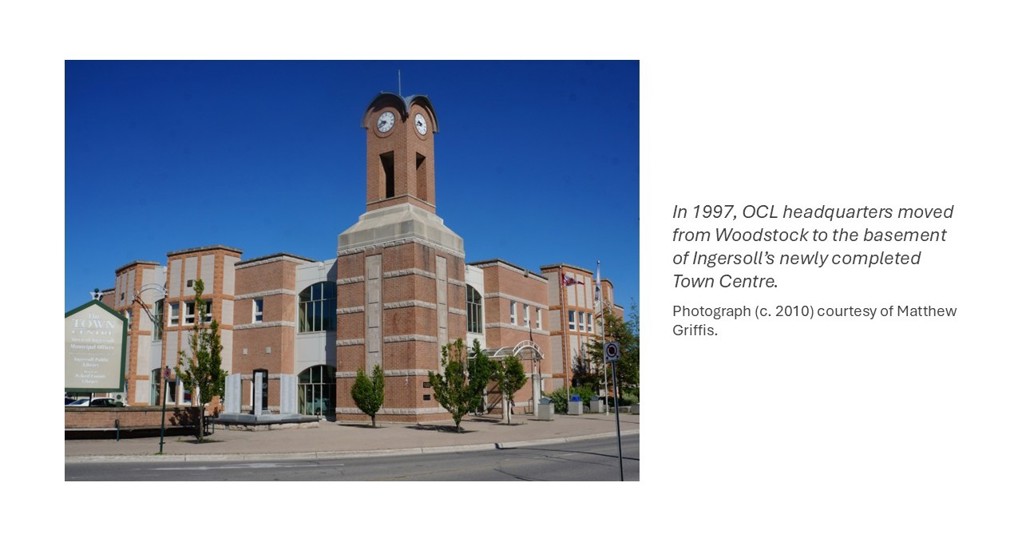

1997 | In February, the Oxford County Library's HQ building in Woodstock closes permanently and the OCL moves its administrative offices to the basement of the Ingersoll Town Centre. (Today, the former HQ building in Woodstock houses Southwest Public Health.)

1998 | With support from Human Resources Development Canada, the OCL launches a project called Information Access Oxford (IAO), which creates an information technology division to support the library and several other units within Oxford County. The IAO helps create the County of Oxford Integrated Network (COIN), a project supported by Ontario’s Telecommunications Access Partnerships program and which provides high-speed internet access to all 17 OCL branches. As County Warden Mark Harrison remarks at the time: “Oxford County is becoming the partnerships capital of Canada!”

1999 | The OCL receives a Minister’s Award for Innovation from the provincial Ministry of Citizenship, Culture, and Recreation for its Information Access Oxford (IAO) project.

6. New Directions (2000-25)

2000-02 | OCL becomes a founding participant ’s in “Service Canada Oxford”, a federal project that explores how effectively libraries can provide government information service to the public. After receiving the same training as government service personnel, OCL staff respond to 7,250 government inquiries over the project’s 27-month schedule. A Treasury Board report later praises OCL staff for “[going] the extra mile” as a standard of service. “Locations staffed by librarians bring a certain professionalism to the access centre,” it concludes. “As by the nature of their work, they are skilled in helping clients search for and find the information they need.” Although public libraries still facilitate access to all kinds of government information, the success of “Service Canada Oxford” eventually inspires the federal government’s Service Canada help centres, which are now common across the country (and rarely far from a public library).

2003 | For the second time in its history, the OCL receives a Minister’s Award for Innovation from the provincial Ministry of Citizenship, Culture and Recreation. This time, the award recognizes the OCL’s contribution to the Service Canada Oxford project.

2004 | In June, Chief Librarian Sam Coghlan leaves the OCL to become Chief Librarian of the Stratford Public Library.

2005 | The Beachville, Drumbo, Hickson, Kintore, and Oxford Centre (formerly East Oxford) branches close permanently.

2006 | Formerly the OCL's Branch Services Librarian, Lisa Miettinen becomes CEO/Chief Librarian of the Oxford County Library. (Miettinen is the first OCL administrator to hold both titles concurrently.)

Norwich's historic Carnegie building at 21 Stover Street closes after serving 90 years as a library. The Norwich Branch relocates to a new facility at 10 Tidey Street.

2009 | The OCL moves its administrative offices from the Ingersoll Town Centre to the newly completed Oxford County Administration Building (OCAB) downtown Woodstock.

2010 | After 93 years as a library, Tavistock's historic Carnegie building closes. The Tavistock Branch relocates downtown, on the ground level of the former Oxford Hotel building at 40 Woodstock Street South.

2012 | Tillsonburg votes to dissolve its library board and join the OCL system effective January 1, 2013.

2013 | On January 1, Tillsonburg joins the Oxford County Library system. Branch operations relocate temporarily to the Tillsonburg Town Centre shopping mall while the former Tillsonburg Public Library building on Broadway Street undergoes substantial renovation. The revamped building reopens in May as the Tillsonburg Branch of the Oxford County Library.

2020 | In response to the COVID-19 global pandemic, the Oxford County Library temporarily closes all its branches effective March 14th. In coming months, and following strict guidelines implemented by provincial and federal authorities, the library’s larger branches resume service but follow reduced hours and offer curbside service only. Some library programs resume but run virtually. By fall, some branches reopen their buildings to the public but masking and social distancing restrictions remain in effect.

2021 | Due to rising numbers of COVID infections across the region, the library reverts to curbside-only service in April. By July, most branches reopen their buildings to the public again, although program delivery continues to be virtual.

2023 | In May, the Oxford County Library launches a bookmobile service called Ox on the Run. Staffed by two full-time clerks and using a former ambulance as its vehicle, the Ox on the Run bookmobile offers reading materials, basic circulation and tech services, and programming.

2025 | The OCL celebrates its 60th year of service with a variety of projects and events. Among them is a brief promotional film titled The Oxford County at 60: Foundations and Future.

Sources

Most information above came from primary sources, including period newspaper articles, scrapbooks, government reports, internal correspondence, and other archival materials in the Oxford County Library's collections. Oxford County Libraries: A Brief History, written by Louise Krompart and published in 1972, deserves special acknowledgement, as does its updated version (which was begun c. 1984-85 but appears not to have been completed). Past issues of the Ontario Library Review (c. 1920s to 1950s) as well as the Inspector of Public Libraries reports, usually published as appendices in the province's Department of Education annual reports, provided further chronological information. We also thank the many former staff members who verified specific information in the timeline's later sections.

The following County of Oxford Archives collections provided further primary source material: the COA001 Leonard K Coles Papers fonds; the COA034 Incorporation fonds, Series 1 Libraries; the COA123 Woodstock-Sentinel Review fonds; the COA250 Oxford Historical Society fonds; and the RG2 Oxford County fonds, Series 24 Oxford County Library. We further acknowledge the Western University Archives and Special Collections, the County of Oxford Archives, and the Federated Women's Institutes of Ontario for allowing us to include images and reproductions of documents from their collections.

For queries, corrections, or any other inquiries about this timeline, contact Matt at localhistory@ocl.net.

Selected Secondary Sources

Bruce, Lorne. Free Books for All: The Public Library Movement in Ontario, 1850-1930. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1994.

Bruce, Lorne. Places to Grow: Public Libraries and Communities in Ontario, 1930-2000. Guelph, ON: Lorne Bruce, 2011.

Forrester, James A. Anderson. “The County Library in Ontario: Topsy Finds a Home.” Research paper, Oxford County Library collections, January 1994.

Krompart, Louise. Oxford County Libraries: A Brief History. Woodstock, ON: Oxford County Library, 1972.

Lewis, M. Rosemary, and Ken Moyer. “History of the Ingersoll Library.” Research paper, Oxford County Library collections, c. 2000.

Ridington, John et al. Libraries in Canada: A Study of Library Conditions and Needs. Chicago: American Library Association, 1933.